When Beliefs Shape Scripture, Not the Other Way Around

I remember sitting in Sunday school one morning when someone confidently declared, “Well, the Bible does say God helps those who help themselves!” Everyone nodded in agreement, but I remember thinking, Wait a second …that’s not in the Bible. It was one of the first moments I realized how easily people confuse familiar sayings, opinions, or traditions with actual Scripture.

Years later, when instead of just hearing it preached to me, I finally started reading the Bible for myself, what surprised me most wasn’t what I found , it was what I didn’t find. So many of the verses I’d heard quoted my whole life either didn’t exist or meant something entirely different in context. It made me wonder how many Christians are unknowingly defending their own ideas while claiming to defend Scripture.

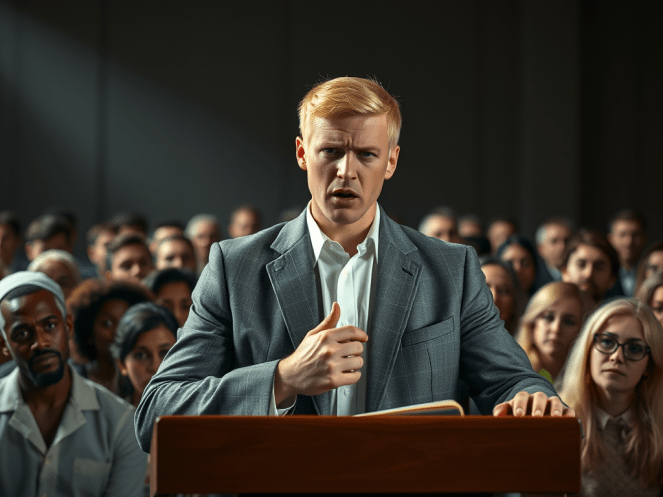

One of the most striking things I’ve noticed since leaving fundamentalism is how often people confidently declare, “The Bible says,” when what they’re really expressing is their belief, not what Scripture actually says. It’s a phrase tossed around like a divine stamp of approval, ending debates before they even begin. Yet many of the people who use it most often have never read the Bible from beginning to end, let alone studied it in its historical, cultural, or literary context. Instead, they’ve inherited a version of “truth” filtered through pastors, teachers, and traditions that reinforce what they already believe.

This pattern isn’t unique to one denomination; it’s widespread across modern Christianity. Many believers learn early on to depend on spiritual authorities to interpret Scripture for them. Sermons, devotionals, and Sunday school lessons become the main way they “hear” the Bible, so much so that their understanding of it often comes secondhand. Over time, the difference between what the Bible actually says and what they’ve been told it says becomes almost invisible. And because their beliefs feel sacred, they assume that Scripture must agree with them.

The phrase “The Bible says” becomes a weapon more than a witness. It’s used to shut down questions, silence disagreement, and justify personal or cultural biases. People quote half-verses out of context or blend biblical language with political talking points, convinced that their opinion carries the weight of divine truth. The irony is that Jesus consistently challenged people who misused Scripture to elevate themselves or oppress others. The religious leaders of His day knew the words but missed the meaning and He called them out for it.

The real tragedy is that this habit keeps people from experiencing the richness and depth of Scripture for themselves. The Bible isn’t a static list of talking points it’s a collection of stories, poems, letters, and wisdom written across centuries, filled with tension, mystery, and beauty. Reading it honestly often leads to more questions than answers, and that’s not a bad thing. It means we’re engaging with it as living text rather than a tool to prop up our certainty.

When people say, “The Bible says,” what they often mean is, “My interpretation says.” The difference between those two statements is humility. The first assumes authority; the second admits limitation. True faith doesn’t require pretending to have all the answers, it requires the courage to keep seeking them, even when the text challenges our assumptions.

In the end, maybe the most faithful way to approach Scripture is not with the phrase “The Bible says,” but with the question “What is the Bible really saying here?” That question leaves room for growth, learning, and grace. It invites us to meet God in the tension between what we’ve been told and what we might discover for ourselves. Because when we stop using the Bible to reinforce what we already believe, we finally open ourselves to being transformed by what it actually says.

Disclaimer: The personal experiences shared in this post are based on my personal perspective. While I chose to leave the IFB to find a more gracious and loving faith, it is important to acknowledge that individuals may have different experiences and find happiness within the IFB or any other religious institution. The decision to leave the IFB does not imply a loss of faith, as faith is a deeply personal and subjective matter. It is essential to respect and recognize the diversity of experiences and perspectives within religious communities. The content shared is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as professional advice, guidance, or a universal representation of the IFB or any religious organization. It is recommended to seek guidance, conduct research, and consider multiple perspectives when making personal decisions or exploring matters of faith.